By Dr. Lewis Brogdon

Executive Director of the Institute for Black Church Studies, BSK Theological Seminary

Over the past six years, I’ve delivered a lecture titled “King’s Dream Turned Nightmare and the Fracturing of America” in university classrooms, at public forums, during webinars, and in my “Life and Theology of Martin Luther King Jr.” courses taught at both undergraduate and graduate levels across the South. This work is deeply connected to my role directing the Institute for Black Church Studies at BSK Theological Seminary, where I help shape theological education for students concentrating in Black Church Studies and partner with churches across racial and denominational lines. Through this institute, we’ve developed both an M.Div. concentration and a graduate certificate in Black Church Studies, while also providing theological training for congregations—including NBCA and CBF churches—on antiracism, leadership, and ministry. Whether in classrooms or sanctuaries, I’ve found again and again that Dr. King’s later work—his warning that the dream had become a nightmare—still speaks with prophetic clarity to the fractured moral and political landscape of America today.

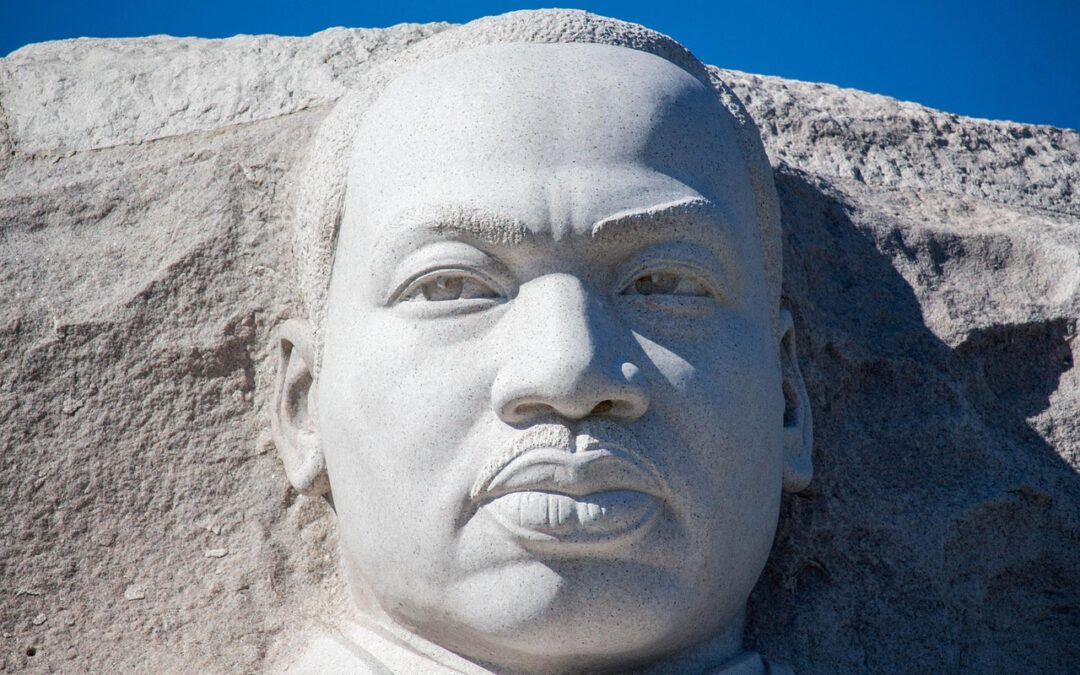

Each time I present it, I am struck by how the figure of Martin Luther King Jr. — while honored with monuments, holidays, and speeches—is still deeply misunderstood. As I’ve argued elsewhere, in my article“The Unknown King” (Virginia Capitol Connections Quarterly, 2019), King remains unknown not because we lack information, but because we’ve refused to engage seriously with his ideas. We’ve built a monument to the dreamer while ignoring the prophet. That neglect has consequences—not just for how we remember history, but for how we live today in a fractured, volatile society King warned us was coming.

The Dream We Remember, the Nightmare We Forget

Most Americans know King through selective soundbites—particularly the soaring conclusion of his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech. But I’ve spent years challenging audiences to reckon with the whole King, especially the man he became between 1963 and 1968. In those years, King’s dream did not disappear—but it darkened, sharpened, and ultimately gave way to what he openly called a nightmare.

In a May 1967 interview with NBC News, just eleven months before his assassination, King stated:

“I must confess that the dream that I had… has, in many points, turned into a nightmare.”

Later that year, on Christmas Eve at Ebenezer Baptist Church, he elaborated:

“Not long after talking about that dream, I started seeing it turn into a nightmare… The first time I saw that dream turn into a nightmare was when four beautiful, unoffending, innocent Negro girls were murdered in a church in Birmingham, Alabama.”

These weren’t rhetorical flourishes. King was naming the profound betrayal he felt from a country that embraced symbols of racial progress while rejecting the substance of equality and justice.

His wife, Coretta Scott King, described that shift in their thinking as well. Reflecting on the Birmingham church bombing, she wrote in My Life with Martin:

“We had underestimated the virulent depth of white hatred… It made us sadly reassess the whole situation.”

That reassessment led King into a deeper critique of America — not just its racism, but its economic injustice, militarism, and moral hypocrisy.

King’s Warning of Chaos on the Horizon

King was not simply disillusioned. He was prophetic — and he warned of the chaos that would follow America’s refusal to change. In his final book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?, he declared that America stood at a crossroads. The chaos he foresaw was not abstract. He saw it already unfolding in the uprisings in Black communities, in the deepening poverty, in white backlash, and in a nation spending billions on war while ignoring the needs of the poor. He wrote:

“When a nation becomes obsessed with the guns of war, it loses its social perspective and programs for social uplift suffer.”

These weren’t distant possibilities — they were imminent realities. And King knew that the dream would remain a fantasy unless the systems creating the nightmare were dismantled.

Rediscovering the Unknown King

In my 2019 article “The Unknown King,” I wrote that America prefers the “dreamer” because it’s easier. King is remembered as a man who inspired hope, not as the theologian and radical critic of American democracy who challenged us to restructure society from the ground up. “There is a difference between looking at a monument and studying a text,” I wrote. “A monument is a symbol. But without the weight of King’s intellectual and spiritual thought, can it make a difference?”

To study King is to enter into a profound moral and philosophical engagement. His writings on nonviolence, direct action, redemptive suffering, and justice are not just history — they are guides for how to confront the crises we face today. In an era marked by mass shootings, racial hatred, economic inequality, political polarization, and cultural estrangement, King’s nightmare is unfolding before us. And many of these issues —particularly the post-Obama resurgence of racial animus, the rise of white nationalist violence, and the ongoing injustice experienced by Black Americans — mirror the very realities King condemned in the 1960s.

The King We Need Now

For decades, I’ve challenged students and audiences alike to do more than celebrate King; I urge them to study him. To read Letter from Birmingham Jail, The Trumpet of Conscience, and Where Do We Go From Here. To encounter the depth of his theology, the fire of his moral passion, and the vision of community that still has power to transform.

King was not just marching for civil rights. He was calling for a moral and spiritual revolution — one rooted in truth, love, and justice. And he knew the cost. He knew that speaking against capitalism, militarism, and structural racism would isolate him, and perhaps kill him. But he believed, even in the shadow of death, that love and justice were worth the cost.

In his final speech, the “Mountaintop” sermon, King gave us a parting word — not a utopian fantasy, but a hard-won hope grounded in struggle. He saw the Promised Land, even if he wouldn’t get there. But he never said we would arrive without pain. Before the dream can be realized, we must first face the nightmare.

Final Thoughts

We have spent decades building a monument to a version of King that America finds comfortable. But monuments don’t save nations — truth does. The dream King spoke of cannot live if the nightmare he exposed continues to be ignored. As I’ve said for years in classrooms and lectures across the South: King doesn’t just belong to history. He belongs to our future. But only if we stop celebrating the parts of him that inspire us — and start listening to the parts that convict us. Only then will we truly know the King we’ve forgotten — and the one we still desperately need.